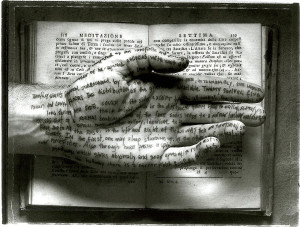

Poetry’s origins are in song and chant that made their impact by sound. It remains, for me, an art of the spoken word: that it’s seen in print on the book page or the computer screen or by Kindle is a convenience but not an end. We need to hear it, in our heads at least.

Poetry’s origins are in song and chant that made their impact by sound. It remains, for me, an art of the spoken word: that it’s seen in print on the book page or the computer screen or by Kindle is a convenience but not an end. We need to hear it, in our heads at least.

I think that helps to explain why I rarely use very short lines. If anything, my lines are getting longer. Very short lines produce a shape on the page that may be pleasing and is most obviously different from prose. The shape itself may be a kind of art as in the diamond-shaped poems beloved of Dylan Thomas and lesser poets. But this is nothing to do with the sound

of the words, and indeed, diverts attention from the sound. Moreover, these forms seem to me to lay claim to a kind of precious exceptionalism, “Oh, look! This is Art!”) that I want to avoid.

The issue is particularly live for poetry that does not rhyme and does not follow a strict system of syllables and stresses such as the iambic pentameter. With such poetry, you can set it out as you choose.

Sorry if this sounds dogmatic. I do occasionally use short lines and they may be the best normal form for some – but not for me.

Let me illustrate what I mean. Here’s a part of a poem I wrote recently (not yet posted here):

What is this place we have come to between the mountains

The shallow hollow just enough for a tent?

You may find a buckle or a tooth and the grey shades cluster

To answer them death, to ride away from them death,

Or maybe you dreamt them as the ravens rose in triumph

As the sun fell and the moon rose and the stars’ fire

Beckoned the wolves’ wail, quietened the hare’s breath.

Now let’s see this as some might present it:

What is this place

We have come to between

The mountains?

The shallow hollow

Just enough for

A tent?

You may find

A buckle or a tooth and

The grey shades cluster

To answer them

Death

To ride away from them

Death

Or maybe you dreamt them

As the ravens rose

In triumph

As the sun

Fell, and the moon

Rose and the stars’ fire

Beckoned

The wolves’ wail

Quietened

The hare’s breath.

To me the former is easily heard with a compelling rhythm, while when you read the latter, the heard voice in the head is lost – and it would be far harder to read aloud!

Written by Simon Banks